Active learning in lectures

Principles guiding active learning in lectures:

- Establish and communicate learning goals.

- Cut down on the amount of content covered.

- Rather than conveying information, focus on analysing issues or problems.

- Use active learning strategies (examples below). Aim for activities that promote higher order thinking such as - recalling, applying, analysing, evaluating, creating, presenting, synthesising and verbalising concepts.

- Aim to do something new at least every 20 minutes. (Berkely, 2018)

If conducting a live-streamed session (LSS) (previously known as BSL-lite), some of the advice in this guide may not apply.

Establishing a culture for active learning

Strategies for active learning in lectures should be planned prior to and set up from the start of the teaching period. Some strategies that can assist in setting up a culture conducive to active learning are:

Explicit expectations on activities

Set expectations that lectures will be active, and that you will be asking students to engage with activities as well as with each other. If consistently using a particular strategy, explain or demonstrate that strategy including any technologies you plan to use. Communicate the level of preparation you are expecting students to bring to the lecture. If prior reading or preparative work is required, outline to students know the types of activities that will relate to that reading or work.

Start with low risk activities

Start with something that allows students to be successful and is low-stakes - particularly if using technology that is unfamiliar. Activities that test complex knowledge, show knowledge gaps or show the student to be wrong are not good places to start (Salmon, 2013).

Ice-breakers

Students are more likely to engage in discussion etc. if they know the people they are sitting with or who are attending remotely. Allow students to learn each other’s names and interests early on with ice-breaker activities. These activities can also help facilitate group/partner work later in the semester. (Yale, 2018).

Discussion ground rules

Have a whole lecture discussion on what are the ground rules for large in-person or online discussions in lectures to ensure an inclusive class climate for all students’ (Yale, 2018).

The first 5 minutes

It is worth spending some time thinking about how you are going to capture students’ attention and focus them in the first 5 minutes of a lecture. This initial period is the golden moment to grab students’ attention and focus - open boldly and ensure that you are well organised.

Communicate goals

Instead of simply telling students the goals of the lecture, open with questions that the students need to be able to answer by the end of the lecture. Ensure that questions generate students’ interest in what you are about to present. One way to do this is to frame the question in a provocative way or create wonder (Lang, 2016).

Retrieval practice

Start the lecture by asking students to summarise the key points from the last session or prework. You could use Poll Everywhere with multiple choice questions or free text responses or use an LMS test. (Lang, 2016). You can also use this technique during the lecture whereby for two or three minutes you ask students to write down everything they can remember from the material you just covered and then discuss issues or misunderstandings. This practice forces students to retrieve information from memory which has many benefits for learning. (Brame, 2016).

Gain understanding of what students already know on the topic

Ask students to respond to the question “what do you already know about…?’, write down their responses for 2-3 minutes, and then discuss responses. This activity can reveal misconceptions, help activate retrieval and allow you to structure the lecture to address any gaps. (Lang, 2016).

Questions related to pre-work

Advise students you will be bringing a student list to the lecture and calling out a name at random to explain a key concept from the reading or pre-work. Advise students that the names called on will be different each week and will not be repeated. Students who are chronically anxious about public speaking should be allowed to contact you to be put on the “do not call” list. (Mulder, Making large lectures more interactive workshop, 2017)

Example active learning strategies

Think-pair-share

This strategy is low-risk and easy to use and is very effective at quickly making your lecture more interactive. Questions are more effective if they require higher order thinking such as analysing or applying. Give students 1 minute to write a response, i.e. “Think”. The “Pair” component requires that the students discuss their responses in pairs for two minutes, critically considering each other’s responses. Finally, students “Share” responses with the wider group while you provide explanation as needed. This sharing of understanding deepens the students’ connections with the content (Brame, 2016; PennState, 2007).

Large group discussions

Whole-lecture discussions can be difficult at first but when combined with an active lecture structure, can be successful. Ask students to discuss a topic in the lecture based on a reading, video, or problem, then use technology such as Poll Everywhere to start a conversation (Yale, 2018).

Snowball fight

Ask students to respond to a question or summarise the learnings from the lecture, writing their answer on a piece of paper. Ask students’ to then screw up their piece of paper into a “snowball.” On your cue, students throw the snowballs around the room as many times as possible, simulating a “snowball fight”. When you stop the snowball fight, each student picks up a snowball and reads the response written on it. Get students to read out responses and discuss. Because students are not reading out their own words, they are less attached to what they are reading out and more willing to share. (Büyüksimkeşyan, 2010).

Pause procedure

Regular pauses during your lecture to allow students to review and discuss notes helps students consolidate learnings, stay organised, and ask for clarity if needed. Research has shown that regular pauses in the lecture increases learning compared to no pauses (Brame, 2016).

Collaborative note taking

After a pause procedure (as outlined above) ask students to exchange notes with a partner and compare and discuss. This allows students to ensure they have captured key ideas and noted any misunderstandings. The instructor can then field clarifying questions (Yale, 2018).

Demonstrations

Including demonstrations is an engaging technique for lectures. Demonstrations are enhanced if you first get students to make a prediction of outcomes and briefly discuss in pairs. After the demonstration, ask them to reflect on results and their prediction and clarify as needed. This activity tests misconceptions and understanding (Brame, 2016; Yale, 2018)

Case study centred lectures

Finding real world case studies to support content delivered engages students and helps apply knowledge to real-world situations. Commonly used in management, law and medicine but can be utilised in other settings (Yale, 2018).

Role playing

Role playing can involve the lecturer role playing a scenario and students commenting and reflecting, or alternately it can involve students’ role playing. Even in large lectures, students can role play scenarios such as responding to interview questions, defending an idea they have just been taught, or being a professional in the discipline responding to client questions. Role playing allows students to embody the knowledge presented providing a deeper learning experience. The activity can be reflected up and discussed (Glover, 2014).

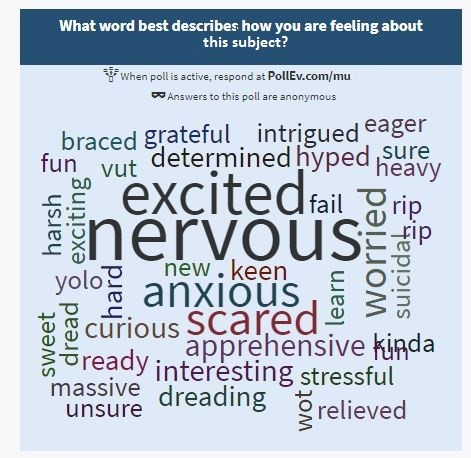

Activities with Poll Everywhere

Poll Everywhere is a useful technology to encourage student engagement in large lectures without requiring students speak in front of large groups. Many of the techniques described above can be facilitated by Poll Everywhere with open-ended questions, whereas the activities outlined below take advantage of the affordances of the technology.

Stimulate discussion

One of the most effective ways to stimulate whole lecture discussion is to use open-ended questions in Poll Everywhere. It is worth keeping in mind however that anonymous responses can potentially lead to inappropriate comments being displayed on the screen, so you may want to make use of moderation so that responses are vetted.

Concept building

Typically during a lecture, you are building understanding of a concept in steps. Asking questions to apply knowledge conceptually as you progress provides a manageable way to build up the understanding of the concept.

Competition poll

Competitions allow you to ask a series of questions and track a leader-board to add an element of friendly competition to check understanding (Broussard, 2018).

Error identification

With clickable images or free text responses you can project statements, images, or other material that demonstrates errors. Students can click on the error or type in the correction to be displayed.

Peer instruction

Use multiple-choice questions to challenge students’ understanding of a concept. Give students a moment to think about their answer and respond but do not show the responses on the screen. Then ask students to discuss their response in pairs. Allow students to then change their answer after the discussion if desired. Display the results and correct answer and discuss as whole group.

Exit test or assess prior knowledge

The survey question type allows you to ask a series of questions which students can respond to. The results are not shown on the screen in order to test students’ understanding. This question type can be used to assess prior knowledge at the start of a lecture or as an exit test at the end of the lecture. Poll Everywhere responses can be anonymous or you can require students to log on with Single Sign-On and track their responses (Beatty & Gerace, 2009).

Jazzing up the presentation component

When delivering the presentation component of your lecture, the ideas below can assist with increasing engagement:

- Storytelling

- Excerpts from movies

- Short video/audio/ animations (ensure Lecture Capture is paused to prevent copyright breech and you provide expectations about why they are engaging with the content and how best to engage.)

- Using objects

- Guest speakers

- Connecting content to current events

- When talking to slides, use the annotation tools to annotate on the slides to make the presentation more visually changing.

The last 5 minutes

Using the last 5 minutes thoughtfully to enhance learning instead of wrapping up in a hurry or shouting out a few quick reminders can aid the effectiveness of the active lecture for learning. Applying a known teaching and learning strategy in the last five minutes can make a difference over a semester.

Closing connections

To allow students to make connections between what was presented and their lives, finish the lecture with a question such as “identify five ways in which the lecture material applies to your world”. Students can write the answers in a collaborative document or a free text Poll Everywhere question (Lang, 2016b).

Minute paper

The ‘minute paper’ technique requires students to spend 1-2 minutes at the end of the lecture writing down a response to the following questions: What was the most important thing you learned today? What questions remain in your mind? Ask students to submit their responses online or in person to you as they leave the lecture. This technique allows students to articulate and consider newly formed connections (Brame, 2016; Lang, 2016b).

The metacognitive five

Students can be poor assessors of their own understanding of a topic or effective strategies for study. Use the last 5 minutes to ask students to spend 5 minutes writing down how they can best prepare for their next assessment. Ask them to share their strategy with you and use it after the assessment to highlight which strategies were most effective (Lang, 2016b).

Close the loop

If you used a strategy to pose a question that they need to be able to respond to by the end of the lecture; revisit the question at the end of the lecture and discuss the new knowledge and understanding.

References

- Beatty, I. D., & Gerace, W. J. (2009). Technology-Enhanced Formative Assessment: A Research-Based Pedagogy for Teaching Science with Classroom Response Technology [Article]. Journal of Science Education & Technology, 18(2), 146-162.

- Brame, C. J. (2016). Active learning. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved 5/11/18.

- Broussard, F. (2018). Add a competitive edge to students' learning with Poll Everywhere. Learning Environments | University of Melbourne. Retrieved 6/11/18.

- Lang, J. M. (2016). Small Changes in Teaching: The First 5 Minutes of Class. The Chroncile of Higher Education. Retrieved 5/11/10.

- Salmon, G. (2013). "The Five Stage Model".

- Yale. (2018). Active Learning | Yale Centre for teaching and Learning. Yale University. Retrieved 5/11/18.

This page was last updated on 23 May 2022.

Please report any errors on this page to our website maintainers