Applying Four-Component Instructional Design (4C/ID) to the Master of Public Health

Background

In August 2020, our team of Learning Environments learning designers partnered with staff from the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health (MSPGH) to design and develop 4 core subjects in the Master of Public Health (MPH) for online delivery. Funded by Chancellery’s FlexAP initiative, the project spanned a period of 12 months and involved a team of 3 learning designers, 20 academic, professional and leadership staff from MSPGH, 3 video producers, 2 web designers and 2 project managers.

Outlined below is the learning design approach pursued and the impact of the work for 2 of these graduate subjects: Epidemiology 1 and Biostatistics.

The challenge

One of the early tasks in the learning design team’s workflow is to identify any recurring issues in the subject reported by learners and teaching staff that could benefit from targeted learning design interventions. Such interventions may include adjustments to the way the curriculum or learning sequence is structured (informed by pedagogy) or/and enhancements to the online learner experience (using educational technology). The most important intervention, however, is applying an evidence-based approach or framework to alleviate the issues that have been identified.

Epidemiology 1 and Biostatistics reported some shared issues:

- The student cohort comes from diverse disciplines leading to mixed expectations and prerequisite knowledge eg. experience in reading scientific papers/journals

- Learners find the curriculum ‘too complex’ (cognitive load)

- The technical aspects of the subjects are challenging as some knowledge of math/statistics is required (prior knowledge)

- In some cases, the principal concepts required to successfully complete assessment tasks and meet learning outcomes (complex cognitive tasks) are not fully understood

- Learners have previously experienced difficulty combining parts of the tasks that they were given (in tutorials) into a coherent whole (fragmentation)

- The real-world contexts in public health are varied and multi-layered requiring broad perspectives - learners have difficulty integrating acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes (compartmentalisation).

Our approach - applying an evidence-based learning design model

To address these issues, we identified the Four-Component Instructional Design (4C/ID) model (Merriënboer, J.J.V 2019) as a suitable approach.

What is 4C/ID?

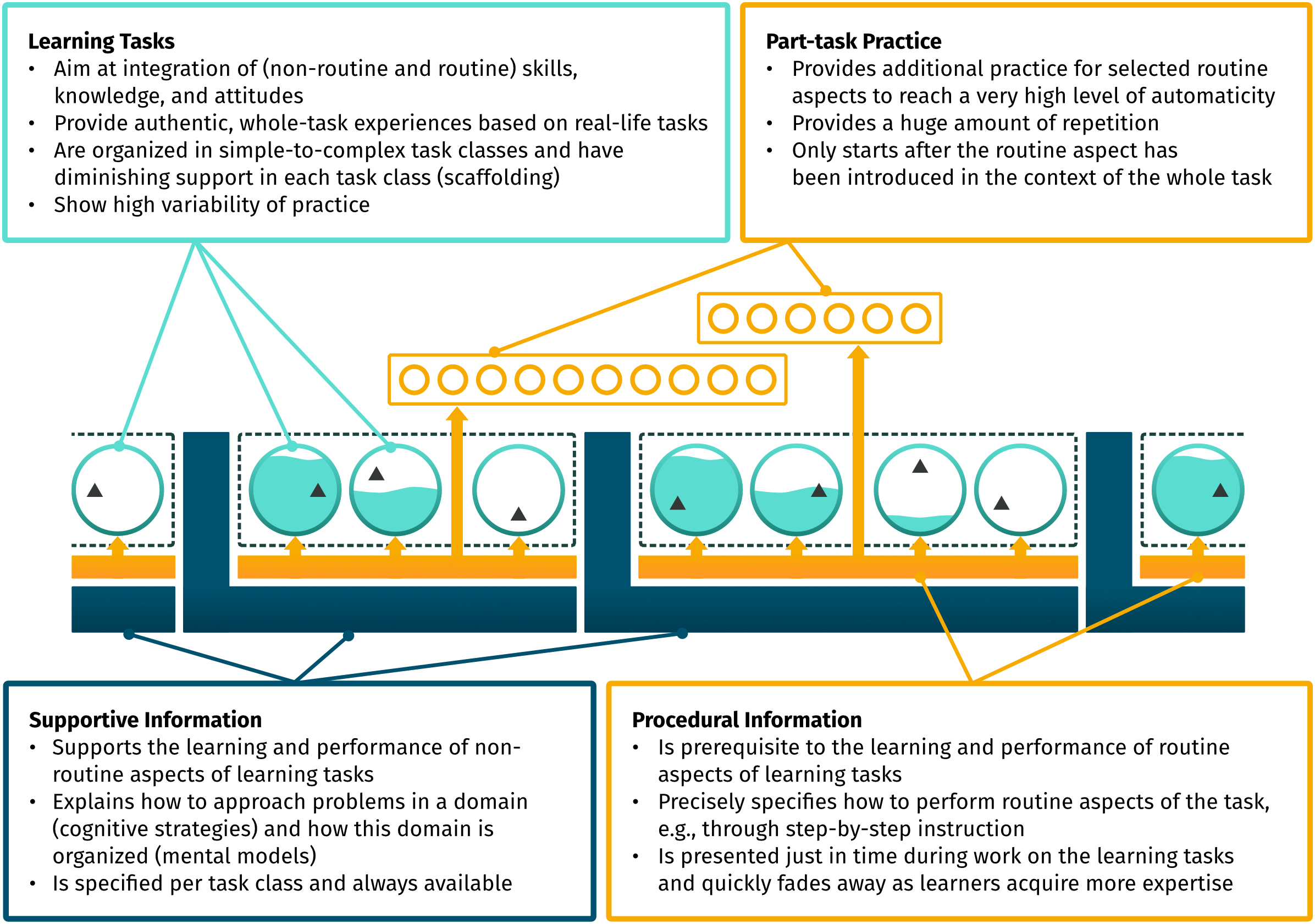

4C/ID has been widely acknowledged as a whole-task approach to learning which supports the development of educational experiences for students who need to learn and transfer complex cognitive skills to an increasingly varied set of real-world contexts and settings (Merriënboer, J.J.V., & Kester, L. 2008). It assumes that educational experiences are made up of four components:

- Learning Tasks: Holistic, authentic activities aiming at integrating skills knowledge and attitudes, organised from simple-to-complex and showing high variability of practice.

- Supportive Information: Resources that provide cognitive strategies and mental models that learners will need to complete their Learning Tasks (this can be equated to the ‘theory’ that is taught).

- Procedural Information: Just-in-time guides that support learners complete the routine aspects of various Learning Tasks.

- Part-task Practice: Opportunities to practice routine aspects and achieve automaticity.

These components can be repeated and extended throughout the learning as needed, depending on the complexity of the whole-task and the number of Learning Tasks needed to complete it.

The image below shows graphically how the four components are organised:

[Available from: https://www.4cid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/4cid_graphic_v2021.png]

Applying 4C/ID

Learning Tasks - creating holistic, authentic activities

The 4C/ID task-orientated approach centres learning around whole authentic problems and professional skills. The approach is effective in reducing challenges faced in these subjects such as fragmentation (not being able to combine parts of a task into a coherent whole) and compartmentatlisation (difficulty integrating acquired knowledge, skills and attitudes) (Frerejean et al. 2019).

4C/ID offers a highly scaffolded and progressive structure and pathways towards the completion of whole-tasks made up of multiple activities or Learning Tasks.

In these particular subjects, each week learners were introduced to one or more cases which provided the backdrop against which the whole task was performed. The Learning Tasks that made up the steps for completing the whole-task increased in complexity throughout the week and, alongside automated feedback, provided the necessary support in order for students to progress with confidence in what they had learnt.

The shift to a task-oriented approach was perhaps the most significant intervention. Traditionally, tasks or activities are reserved for face-to face tutorial settings where consistency in tutor facilitation and learner attendance is highly variable and opportunities to practice are confined within the time limits of a rigid schedule. This means it is harder to complete whole (complex cognitive) tasks within these limitations. The application of 4C/ID’s task-oriented approach in this case provided learners with more opportunities to complete authentic activities and the asynchronous mode of delivery allowed further flexibility for learners to revise, practice and apply knowledge and skills, minimising cognitive load and relying less on prerequisite knowledge.

Supportive Information - providing resources to support learning

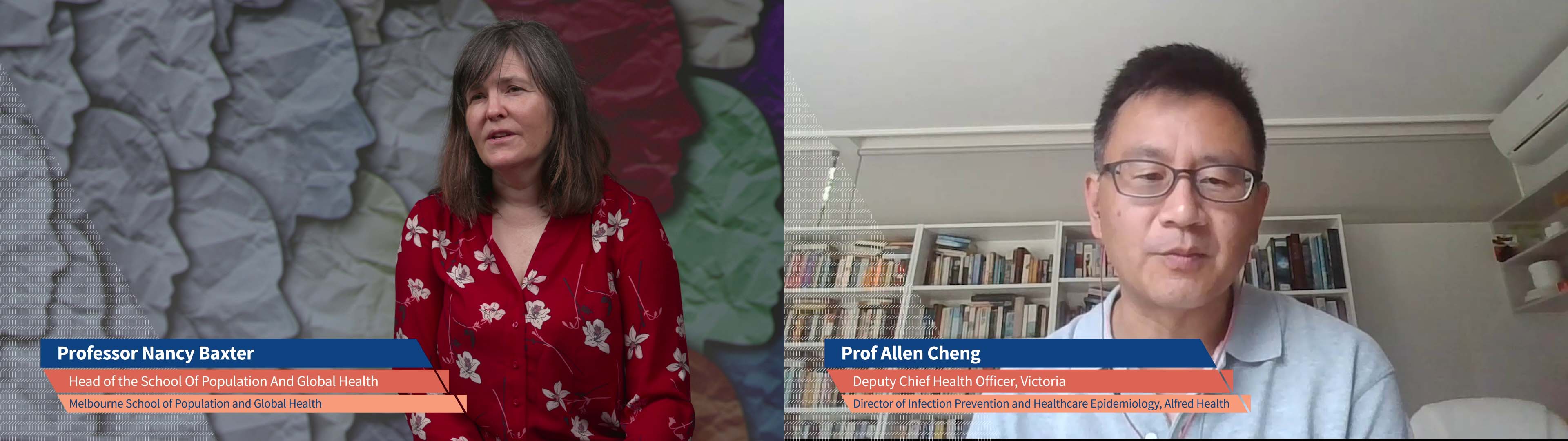

The Supportive Information component consisted of mostly written materials as well as some self-recorded and third-party videos to deliver the bulk of the ‘theory’ (cognitive strategies) while the scope allowed by FlexAP funding was reserved for high production value videos of discipline experts sharing their experiences in solving similar problems (mental models). In total, 19 videos were produced for these two subjects out of a total of 37 videos produced for all 4 subjects

This marked a significant shift from the way this content had previously been taught. Traditionally done though campus lectures and tutorials by the teaching staff with some opportunities for guest lectures, the learning materials are now available and accessible at any time (including for revision) and are scalable, while allowing for more opportunities to include expert voices in a purposeful way (without the need to invite experts each year).

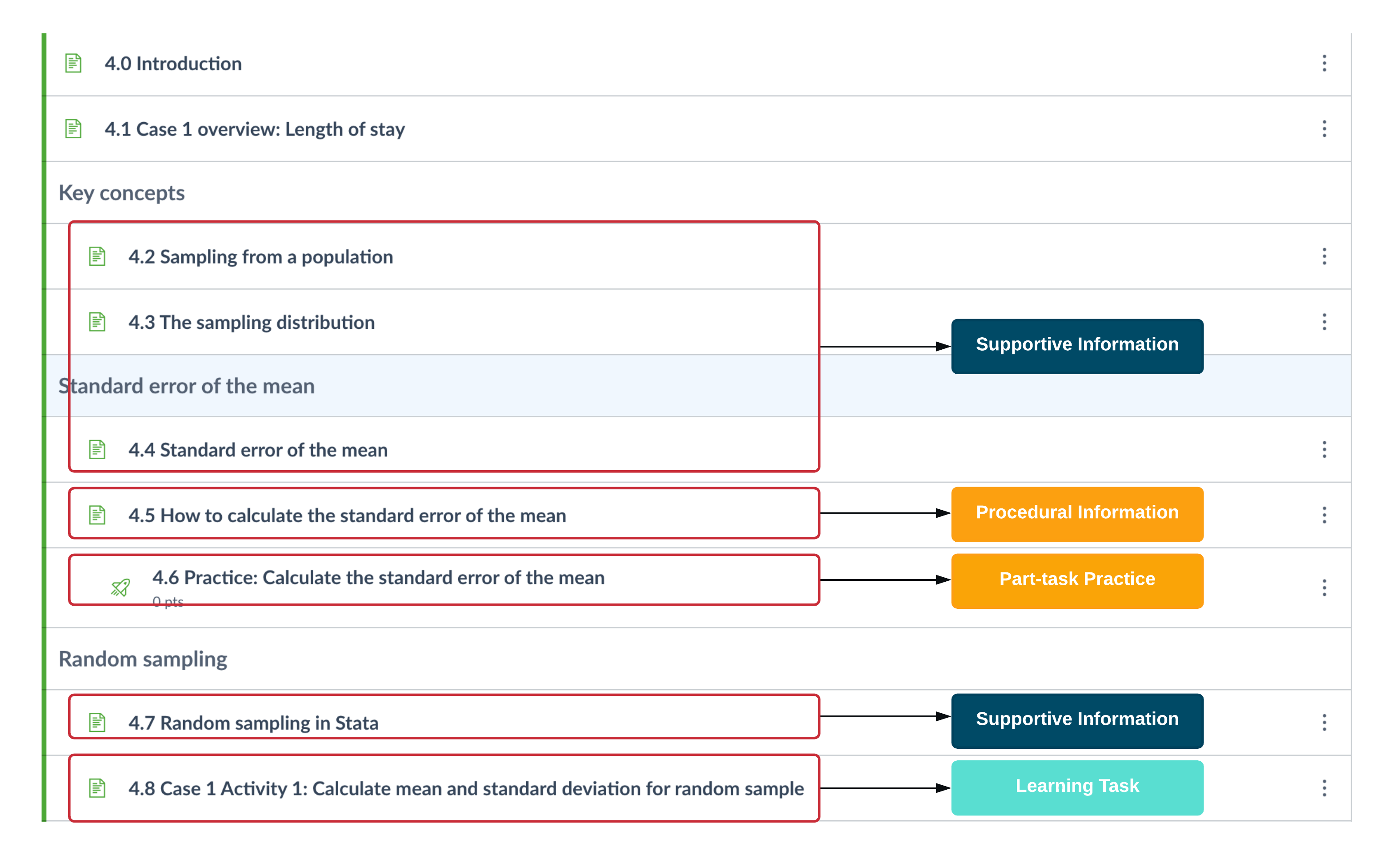

Procedural Information and Part-task Practice - providing resources and opportunities for practice

The Procedural Information component played a key part in Biostatistics. Learners are expected to learn to use Stata, (software used in statistical analysis) so this was achieved with just-in-time instructions on ‘how to’ make use of the software’s commands to complete the associated Learning Tasks.

In the case of Biostatistics, this meant retiring the established practice of scheduling 4 Stata labs per semester where all skills were taught and practiced. Instead, the practice sheets (Part-task Practice) available to support the Procedural Information gave learners more flexibility to learn the skills they need for each task, spreading skills acquisition across the semester and reducing cognitive load.

Using predominantly LMS Quizzes as the mechanism to deliver Part-task Practice activities (as well as the Learning Tasks) enabled automated feedback and the opportunity for learners to practice the activities as many times as they needed. It also allowed teaching and professional staff to measure the access and completion rate of these activities overall through ‘New Analytics’ in the LMS.

Design and development

There are many examples in literature which outline the application of 4C/ID in various disciplines (Frerejean et al. 2019) and the blueprints that have been developed (van Merriënboer, Clarke and de Croock 2002) to help drive the process of implementing 4C/ID.

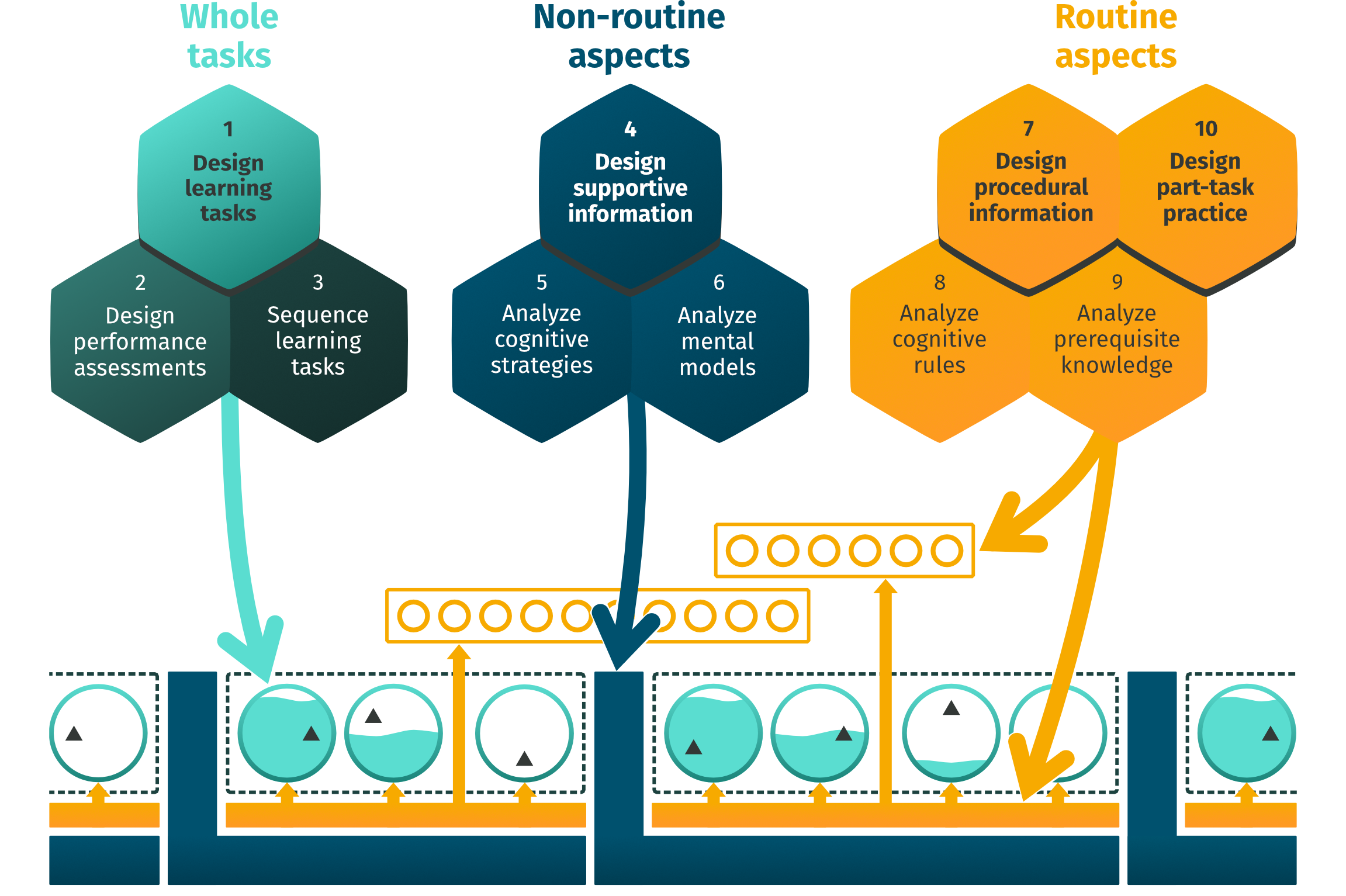

The model’s author recommends a 10-step process for applying the model as outlined below:

[Available from: https://www.4cid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/tensteps_graphic_v2021-1.png]

The first step involves capturing the whole-tasks and associated Learning Tasks in the optimal sequence (increasing in complexity). The next step is concerned with the design of the non-routine aspects – the Supportive Information that covers the background and knowledge (cognitive strategies) and approaches (mental models). Finally, the materials covering the routine aspects are developed – Procedural Information and Part-Task Practice covering ‘how to’ solve problems or follow procedures and plenty of practice opportunities to automate these skills.

To help streamline this process the learning design team adopted the recommended approach and developed the necessary documentation to capture the learning materials within the model’s principles. Regular workshop meetings assisted the progression through the various steps.

In practice, the model was not applied in it strictest and purest sense throughout the subject – affordances were made depending on whole-tasks planned for each week (some could not be effectively broken down into smaller components and therefore multiple smaller whole-tasks were implemented) - but overall, the 4C/ID structure and principles were maintained. The model allows for this adjustment as it does not restrict its application to a predetermined length, size or duration of learning experience.

The impact

Feedback from teaching staff

In addition to changing teaching mode (from synchronous face-to-face to asynchronous online), the interventions outlined above have an inevitable impact on teaching practice.

Epidemiology 1 subject coordinator Ankur Singh commented that:

“The 4C/ID model of teaching provided the rich but complex epidemiological concepts the essential delivery mechanism for students who were new to public health. Rather than one person pretending to know everything in epidemiology, it offered an opportunity to bring together experts across a range of epidemiological concepts, a limitation with traditional teaching methods particularly when applied to a large cohort of students. The tasks ensured that students were engaged and acknowledged the real-life application of concepts that they were learning. The team-based approach towards adopting this new pedagogical technique was particularly helpful.”

Biostatistics subject coordinator Anurika De Silva said that:

“Even though at the beginning there was some apprehension among students about online learning, I am happy that our subject modules were able to help them through that. The Biostatistics team spent a considerable amount of time with the Learning Environments team developing and perfecting the subject modules, which the students said were clear, interesting, comprehensive and easy to follow. We received fantastic teaching scores and feedback from the students, which reflects how well this new mode of teaching was perceived by the students.”

Evaluating the impact on students’ learning

The Learning Environments and teaching teams evaluated the completion rates of Learning Tasks in the LMS as well as capturing further data through two surveys – a student satisfaction survey conducted by the teaching team and a design-focused evaluation (Smith, C. 2008) by the learning design team.

Completion rates for the Learning Tasks (non-compulsory, formative activities) across the semester ranged between 70%-78%. This is in stark contrast to the perception that learners will not ‘engage’ with asynchronous online activities if they are not graded or set as compulsory. The purposeful design of scaffolded activities combined with progressive, just-in-time support to complete them is likely to have contributed to this improved activity completion.

The surveys revealed that learners recognised and appreciated the way the subject was structured and that the interventions made supported their learning. Comments on potential improvements included furthering the use of video and refining the written materials while others commented positively on the flexibility they were afforded, the clarity of the subject structure in the LMS and the commitment and support of teaching staff.

This latter comment is a good reminder that alongside evidence-based learning design interventions, teacher presence is paramount to learner success. While in largely asynchronous online subjects teacher presence manifests in different ways, it is recognised and appreciated by learners none the less.

Direct comments from learners to the teaching team also revealed an increase in request for (offline) access to the learning materials during semester and beyond the completion of the subject for several different reasons. In this light we will consider providing options for offline viewing to support learners who have additional needs related to accessibility or poor internet connections.

Conclusion

At the end of our FlexAP partnership with MSPGH we discussed the experience of working together and how this can be improved. While there is room for improvements in workflow and defining stakeholder expectations, the School has seen positive outcomes from the partnership overall. Some staff, who have since moved to coordinate different subjects within the MPH, have now applied 4C/ID principles to these which demonstrates that good practice evidenced by positive outcomes will spread in other areas of the School, directly benefiting learners.

The Learning Environments learning design team has appreciated the openness with which this approach was received by the MPH team. Learning design works better in partnership with faculties and throughout this project we have felt that our learning and teaching expertise has been valued and a trusted working relationship has formed.

Finally, while the work described here applies to subjects delivered online, 4C/ID is by no means a model exclusive to online learning and can be applied to a wide range of teaching modes, from whole subjects taught on campus or/and individual face-to-face lesson plans. The model has proven success in diverse disciplines and can be applied to introduce (or enhance existing) authentic whole-task approaches irrespective of the delivery mode that is adopted.

Keen to know more?

If you would like to know more about how to apply 4C/ID to your subject please contact Learning Environments.

The teams

- Learning design: Alex Tsirgialos, Kate Mitchell and Fiona Broussard

- Video production: Jamie Morris

- Educational technology: Tim Blundell and Dean Collett

- Project management: James Wooldridge and Dale Bell

- Epidemiology 1: Dr. Ankur Singh, A/Prof Melissa Russell and Prof. Dallas English

- Biostatistics: Dr. Anurika De Silva, Dr. Megha Rajasekhar, A/Prof. Enes Makalic, Prof. John Carlin and Prof. Julie Simpson

- MSPGH leadership: A/Prof. Rosemary McKenzie and A/Prof. Helen Jordan

- With assistance from Learning Environments Senior Learning Analyst Consultant: Damian Sweeney

References

Van Merriënboer JJG (2019) The Four-Component Instructional Design Model - An Overview of its Main Design Principles, School of Health Professions Education, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, The Netherlands

Van Merriënboer, JJG., & Kester, L. (2008). Whole-task models in education. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. J. G. van Merriënboer, & M. P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (3rd ed, pp. 441–456). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum/Routledge.