Providing feedback to students

This article presents frameworks and strategies for integrating effective feedback into subject design and activities, with the aim of achieving high quality self-regulated learning for students and maximising time efficiencies for teaching staff. It focuses primarily on seven principles of best-practice feedback, originally proposed by David Nicol and Debra MacFarlane-Dick (2006).

Why is feedback important?

Effective feedback can help students develop accurate perceptions of their abilities and establish evaluative judgements about the progress of their learning (Taylor and McCormack, 2004). In this way feedback assists students to become self-regulated learners. However, giving and receiving feedback is ‘not as easy as it appears’ (Piccinin, 2003) and delivering effective feedback can be a complex task, particularly due to the ways in which students receive feedback (Bennett, 1997, cited in Taylor and McCormack).

When feedback is poorly timed, vague or person-focused rather than task-focused, students receiving feedback on an assessment task can feel embarrassed and dejected and that the feedback does not relate to other learning needs (Taylor, McCormack, 2004). For teaching staff too, providing feedback can be time-consuming and stressful.

How to provide effective feedback

In his article on improving written feedback in tertiary education, David Nicol (2010) suggests that when designing learning activities, feedback should be incorporated as a contingent two-way process. This involves teacher-student and peer-to-peer interaction, as well as students actively constructing meaning from the feedback they receive. Nicol focuses on introducing forms of dialogue into feedback instead of only providing one-way written feedback from the teaching staff which he describes as a monologue.

Nicol’s perspective arises from a constructivist approach to learning (for example, Vygotsky, 1978; Barr and Tagg, 1995; Palimscar 1998), where it is understood that effective feedback should trigger an inner dialogue in the mind of the student regarding the relevant disciplinary constructs. This allows students to derive meaning from feedback and develop awareness of how to apply this feedback to improve future performance by comparing current progress against desired goals (Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick, 2006).

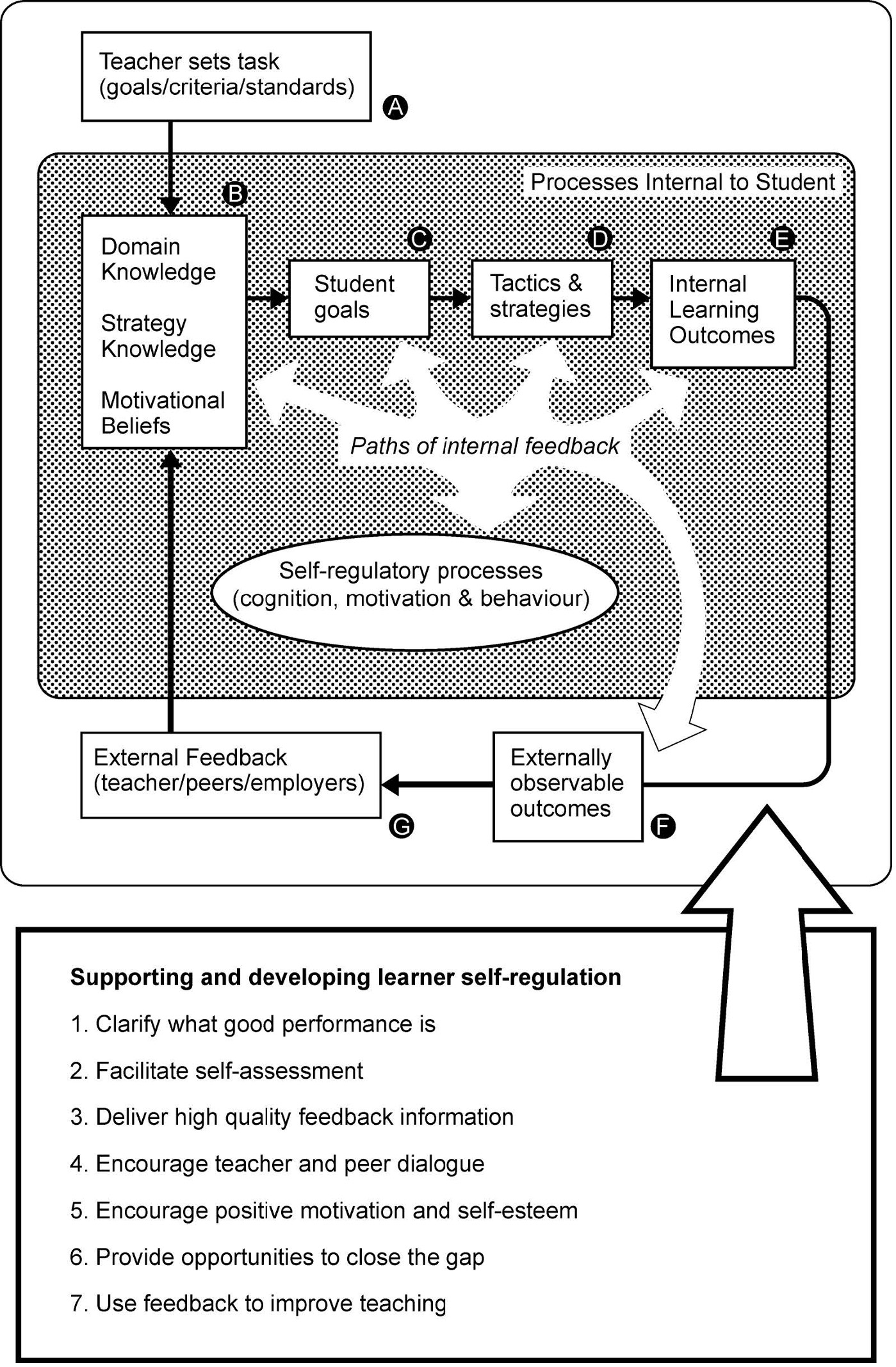

To facilitate student’s capacity for self-regulated learning, Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick propose seven principles for good practice, which are detailed below. Also presented below is a diagram illustrating their model for self-regulated learning. This model has been informed by the seminal pedagogical research of Deborah Butler and Philip Winne (1995) (Fig 1).

Seven principles for good feedback practice

- 1. Help clarify to students an understanding of good performance

When there is different understanding of assessment goals (criteria and standards) between teaching staff and student, feedback is unlikely to be constructive. Effective feedback not only helps students achieve their academic goals, it also plays a role in clarifying what these goals are (Sadler, 1989). To avoid misunderstanding of assessment goals, make the goals of the assessment task (formative/summative) explicit, explaining how they relate to the assessment criteria. Provide an example of a valid standard against which students can compare their work.

Rubrics are one way to help communicate to students what is good performance and calculating rubrics are available in LMS assignments, FeedbackFruits assignments, Gradescope assignments and Cadmus assignments. One activity that fosters a rich dialogue on what constitutes good practice is working with students to create the rubric or the assessment brief.

- 2. Facilitate the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning

To develop students’ capacity for self-regulated learning, create structured opportunities for self-monitoring their progression towards the learning goals. Introduce self-assessment tasks encouraging students to reflect on their progress in relation to the criteria and standards. For example, prior to students submitting their activities for teaching staff feedback:

- Ask students to identify strengths and weaknesses of their works-in-progress in relation to the pre-defined task criteria / standards.

- Provide opportunities for students to evaluate and provide feedback on each other’s work.

- FeedbackFruits allows peer-to-peer feedback using comments or rubrics with the Peer Review and Group Member Evaluation assignments. Most FeedbackFruits assignment types also allow staff to set a reflection activity for students to complete on submission or after feedback is received.

- 3. Deliver high-quality information to students about their learning

Teaching staff are more effective at identifying mistakes or misconceptions in students’ work than their peers, therefore teaching staff feedback is helpful for substantiating student self-regulation (Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick, 2006). Widen your feedback to include correct advice as well as praise and constructive criticism (strengths and weakness of the submission), while explicitly relating these points to the tasks’ learning goals, criteria and standards.

All our assessment tools support the delivery of high-quality feedback by allowing teaching staff to easily give feedback on a document via annotations, via rubrics and provide overall comments, with many also having the option of video feedback.

- 4. Encourage teaching staff and peer dialogue around learning

Nicol suggests dialogue as a way of improving the efficacy of feedback, where students have opportunities to engage in discussion with both the teaching staff and peers regarding the received feedback. Once students have received feedback on their task, two-way engagement can be achieved in either small and large cohorts by using:

- Small break-out discussions (face-to-face or online using Zoom breakout rooms).

- Polling tools such Qualtrics, Poll Everywhere, LMS Survey / Quiz, allowing teaching staff to present overall feedback to students, which can be used as a prompt for class discussion.

- LMS Discussion forum or Zoom chat, where students can ask questions about their feedback (synchronously or asynchronously).

- LMS SpeedGrader allows teaching staff to annotate a student document with feedback as well as leave overall comments. Students have the ability to reply to these comments, however staff need to be aware that they need to return to SpeedGrader to review these comments. Similar functionality is also available through the FeedbackFruits Assignment Review tool.

- FeedbackFruits allows peer-to-peer feedback using comments or rubrics with the Peer Review and Group Member Evaluation assignments. Most FeedbackFruits assignment types also allow staff to set a reflection activity for students to complete on submission or after feedback is received.

Other ways to engage students in dialogical feedback processes (both before and after task submission) are to have students discuss feedback in small tutorial / groups / breakout rooms. These interactive activities could include:

- Student discussion of the learning /assessment criteria and standards at the beginning of the project, particularly helpful in group projects.

- Students provide feedback on each other’s work in relation to the specific task criteria and standards (before submission). See the online tools Feedback Fruits and LMS assignments (when setup for peer review) for further information on how to achieve this.

- Student suggestions as to how they can improve their performance next time.

- Students present one example of feedback they found helpful/unhelpful and why.

- 5. Encourage positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem

Motivational beliefs and self-esteem play a significant role in feedback. It has been shown that students’ motivational frameworks are dependent upon their beliefs about learning (Dweck, 1999). For example, students who believe that ability is fixed and therefore has limitations on what can be achieved through their learning will be less likely to understand and apply feedback successfully, than students who believe that learning outcomes are directly related to effort and engagement with tasks (Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick, 2006). Kozar and Timmins (2018) suggest discussing ‘fixed mindsets’, which can hinder how students understand and apply feedback.

It is important to explain to students that feedback is an evaluation of the submitted work, or the performance of the work and not the person. To facilitate this focus, language such as ‘the work is…’, rather than ‘you are…’ can be helpful. Using a ‘sandwich approach’ to deliver a mixture of constructive positive and negative feedback can be effective (Naylor, Baik, Asmar and Watty, 2014). It has been shown that this mixed approach makes students more likely to accept negative feedback in a constructive way, rather than being disheartened (Poulos and Mahony, 2008, Ferguson 2011).

Motivation and self-esteem are more likely to increase when a subject incorporates several low-stake formative or practice assessment tasks throughout the semester rather than having only high-stake summative tasks, where students tend to focus on how their grades relate to those if their peers. Formative assessment tasks provide opportunities for students to reflect and apply their feedback onto to the task (formative or summative).

Strategies for embedding feedback into formative assessment can be achieved through:

- Nested assessment – develop scaffolded assessment tasks, where feedback from earlier tasks informs the performance /completion of later tasks (for specific examples, see Good Feedback Practice – an MCSHE guide to enhancing feedback for students, p 8).

- Peer review (using tools such as LMS assignments (when set to peer review), Feedback Fruits and LMS Discussion forums).

- Allowing students to re-submit (helps modify student expectations around the purpose of the learning task).

- Formative assessment with automated feedback, for example LMS quizzes and H5P activities.

- 6. Provide opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance

How can feedback effectively change behaviour and lead to higher-level learning outcomes? To answer this question, we need to know if and how students are applying their feedback into future tasks, for example, re-submission, scaffolded formative/summative assessment (Nicol, 2006; Boud, 2010). David Boud presents two ways to close the gap between current and target performance:

1. Support students during the completion of a task. For example, preparing for a case-study presentation or writing an essay. Activities such as LMS quizzes or grouped peer review (using LMS assignments or FeedbackFruits) can generate concurrent feedback that students can then apply into their related individual tasks.

2. Generate an interrelated cycle between task, performance and feedback. For example, re-submission, iterative and scaffolded tasks, project plans and proposals, and essay structures.

As Nicol notes feedback should support both processes: ‘it should help students recognise the next steps in learning and how to take them, both during production and in relation to the next assignment’ (Nicol, 2006).

Additional strategies for closing the gap between current and targeted performance are:

- Provide model examples of the task. For example, how to structure an essay or project plan.

- Embed specific small tasks/points for students to action within their feedback

- Use groups to engage students in discussion around these specified action tasks/points.

- 7. Provides information to teaching staff that can be used to help shape the teaching

In addition to assisting students, effective feedback can provide helpful information for teaching staff to tailor their subjects to achieve higher learning outcomes. It is widely reported how performance feedback from frequent diagnostic activities throughout a subject allows teaching staff to adapt their subject content accordingly (Nicol, 2006; Steadman, 1998). Reviewing and reflecting on feedback data relating to how students are progressing (for example through LMS SpeedGrader, New Analytics and Quiz Statistics, LMS assignments and Feedback Fruits) can assist teaching staff in providing additional support materials or modifying the task design, for future iterations of the subject.

Additional strategies for the collation of student feedback data to help inform teaching are:

- Discuss with students any challenges / difficulties they experience during an assessment task.

- Ask groups of students to compose and present questions they believe would help them for future performance of related tasks.

Nicol’s ‘seven principles’ present a very thorough framework for effective feedback and self-regulated learning. They are however not an exhaustive list for how best-practice feedback can be embedded into teaching and learning. Additional research and strategies for effective feedback can be found via the links below: